A buffet of things to read…

(The big one)

Flavorama: a guide to unlocking the art and science of flavor

Why should a restaurant start a lab? Why would chemists or agronomists collaborate with chefs? So much about food innovation in contemporary restaurants and beyond only makes sense if you look under the Naturalist surface and look at how food technology and food culture have co-evolved in the last 50 years. I presented this paper at the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2019: Food and Power. The full Proceedings are available from Prospect Books here.

Some effects of a wildfire are visually arresting. Others are invisible, dormant for months, and then, suddenly, smellable. You may not have heard of it yet, but winemakers fear its name: smoke taint.

MOLD magazine: What we talk about when we talk about flavor

How is it possible to do good design work with food, that is sensorially engaging and even delightful, without being flimsy or flip? Fortunately, the grounding answer lies in flavor itself—a phenomenon which naturally and fluidly connects the bigger, systemic aspects of food with its personal, visceral and psychological aspects. MORE

Are We Not Dinosaurs? A: We Are Chicken! from Lucky Peach: The Chicken Issue

Los Angeles Times

Onion ash, burnt coconut and seaweed — restaurants in L.A. and around the world get creative with flavored oils

The phrase "flavored oils" might conjure images of Italian-ish garlic and herb oils, chile oils to dress Sichuan dishes or maybe supermarket truffle oils. But there are some new players on the scene that are changing the concept: deep green pine oils and dill oils, intense and dimensional rose oils, oils flavored with not-previously considered-edible things such as aromatic woods, onion ash or hay. In the kitchens of creative restaurants around the world, infused oils let cooks add a precise dose of concentrated, blendable flavor to any dish. Think of them as a customizable, flavor-capture-and-delivery technique — or maybe cocktail bitters for food.

Know Thy Scientist

MAD Dispatches, 2014

Now more than ever, knowledge is being recognized as an essential component of creativity and craft in the professional kitchen. New York restaurant Blue Hill has a maxim: “Know Thy Farmer.” Or, put less pithily, that chefs have a lot to gain by working collaboratively with the folks who know the most about produce—those growing it. The logic being that working with those who provide their raw materials provides chefs with better crops as well as new knowledge that can inform their cooking. Relying on the farmer’s expertise as a guide towards new and potentially interesting products, like aged carrots or long-lost heirloom grains, enhances creative and aesthetic freedom in the kitchen.

This all stands to reason and farmers have taken on an increasingly essential place in the professional kitchen, but this isn’t the only expansion of a chef’s circle of advisors that will improve food both inside and outside the restaurant. The same type of renewed, recast relationship between chefs and scientists will be essential for continuing to advance the craft of cooking though knowledge, and improving the place of food in the world.

Chef Wylie Dufresne put it succinctly in his MAD lecture a couple of years back: “Understanding why you’re doing something is an important aspect of doing it well; there will never be a right way to poach an egg, there’s only a more or less informed way of poaching an egg.” Science and scientists are as yet poorly utilized sources of information that, when directed correctly, can become invaluable partners to chefs in the effort to understand and hone their craft. read more

#wednesdaynightwineclub ponders the question: are wine flavor descriptors bullshit?

Lucky Peach, 2017

Wine is fun and delicious and gets you loose in style. It’s also enigmatic, a record of the inter- play of humans, landscape, fruit, yeast, and a multitude of other contributors over long periods of time. And so while everyone can agree that wine is deli- cious, there are many long-standing, passionate, semi-drunken debates over exactly what tastes so good.

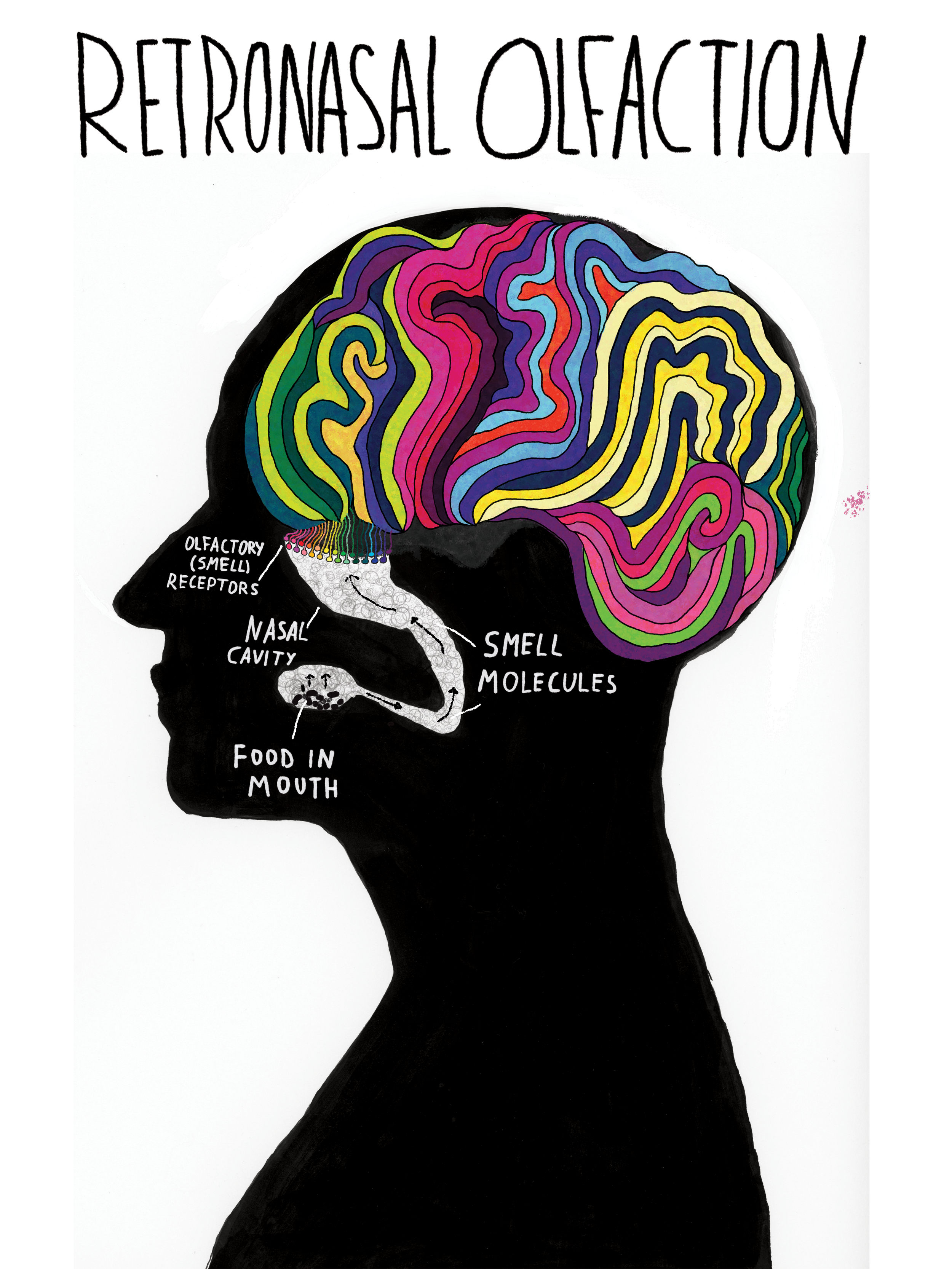

Flavor is what we’re all after—it

is what separates a mediocre cheese from an amazing one, an indifferent coffee from one worth twenty dollars a pound, and the wine that you drank as a broke college student from what you order at Per Se.

Humans have sensitive biochemical systems for experiencing flavors, but

it can be challenging to find the right words to describe those experiences. Anyone who has floundered at a coffee cupping or wine tasting while other participants rattle off “not orange candy, but candied orange” and “peach pound cake” and “reading an old book in a leather armchair in front of a fire” knows what I’m talking about. A paper I like

in the Annual Review of Psychology puts it like this: “Humans are astonishingly good at odor detection and discrimina- tion; humans are astonishingly bad at odor identification and naming.” read more

A Field Guide to Fermentation

A guidebook for cooks of all backgrounds to learn fermentation, built on the ongoing iterative fermentation program at noma. read more

Perceptual Characterization and Analysis of Aroma Mixtures Using Gas Chromatography Recomposition-Olfactometry

PLOS One, 2012 read more

Smells Like Green Spirit: CHEMICAL WARFARE, DISTRESS SIGNALS, DEATH, AND DELICIOUSNESS: PLANT SMELLS WE SHOULdN’T LIKE, BUT WE DO

Lucky Peach, 2015

since you’ve scrolled this far, consider joining the 20 deranged individuals who’ve read my PhD dissertation on Flavor Chemistry and Gastronomy